Orchestration – Preliminary Considerations

REMARKS ON INSTRUMENTS

Before proceeding to our discussion of orchestration per se, a few general comments on the roles of the orchestral families are necessary, as well as some specific advice about how to treat them. Since any student studying orchestration should have already mastered basic harmony – and consequently the norms of four part choral writing – a useful point of departure is to compare each instrumental section with the vocal choir. For students more familiar with the piano, the point of departure should be comparison with that instrument.

Strings

Like the vocal choir, the string family offers excellent homogeneity of timbre, and can play anything from the simplest monophonic line to the richest polyphony. Virtually anything that is suitable for choir will also sound well in strings. However, strings add numerous resources to those of the vocal chorus, due to their much wider range, their much greater mobility and more varied articulations, and their capacity for playing chords.

Unlike choral writing, string writing normally abounds in crossing. This allows the lower instruments to play the main line from time to time, and, most importantly, gives all the individual sections in the family freedom to move, since string instruments’ ranges are so much wider than those of voices. Given the easy blend within the family, such crossing creates no special problems.

Adagio Symphonique: The violas first cross over the 2nd violins, and then the 1st and 2nd violins take turns carrying the leading line. This freedom of partwriting creates a dialogue which adds to the music’s intensity.

A note concerning strings playing pizzicato: they are best thought of as percussion sounds. While produced by string instruments, they have no timbral affinity with bowed strings.

Woodwind

Woodwinds, due to their various distinctive timbres, can provide intimate solo effects. A good policy is to consider each woodwind as being three instruments in one: a high, a middle, and a low timbre. Combinations that work well in one register can be quite odd in another. Also, each type of woodwind is, in effect, a member of a separate choir: For example, clarinets are available from contrabass to piccolo. (The double reeds, oboe, English horn and bassoon, can be considered as one family.)

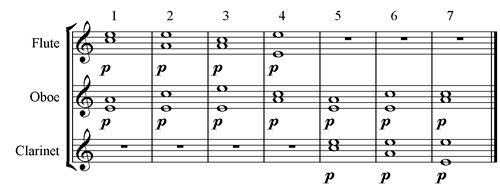

There is a qualitative change when a line is assigned to two or more of the same instrument in unison. This is much more significant than the quantitative one: Three oboes are not even twice as loud as one, but the quality of sound becomes that of a little chorus, due to unavoidable differences in intonation. A line whose character requires a solo sound will be less effective when doubled, due to this difference in character.

![]()

First we hear this melody for one oboe, then for three in unison.

The main problem in writing for woodwinds occurs when they are used in chords, due to their disparity of timbres, both within individual instruments (in different registers) and between them. The common beginner’s mistake, of writing a chord with each note in a different timbre – e.g. four timbres for a four note chord – is very crude. The classical methods suggested by Rimsky-Korsakov – overlapping and enclosure – work by making it difficult to decipher who is doing what, in effect fooling the ear.

None of these chords blends in the way a string or a brass chord would. However the stacked arrangements (#1 and #5) are the worst, especially since the oboe’s dissonant 4 th sticks out. The best blended versions (relatively speaking) are the overlapping ones (#2 and #6).

When writing for massed woodwinds, the oboe is the instrument most likely to hurt the overall blend. It will definitively color any combination, for better or for worse.

These two chords contain exactly the same notes. The 2nd chord, scored with oboes, is considerably more pungent. Both could be useful, in the right context, but the one with oboes has a more distinct character.

When used in the same plane of tone with strings, the main function of woodwinds is to add volume (“thickness”).

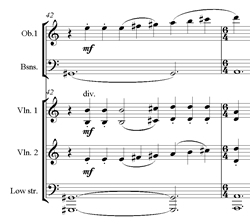

Symphonic Movement #1: The wind doublings of the moving lines in the strings make them thicker and more substantial.

Sometimes, when doubling strings an octave higher, woodwinds can add luminosity.

Symphonic Movement #3: The oboe doubling of the line in the 2nd violin helps it to emerge more clearly, and makes it brighter.

When used in chords, in the same plane of tone with the brass, the winds’ main function is to complete the top of the harmony above, since doubling at the unison is virtually imperceptible.

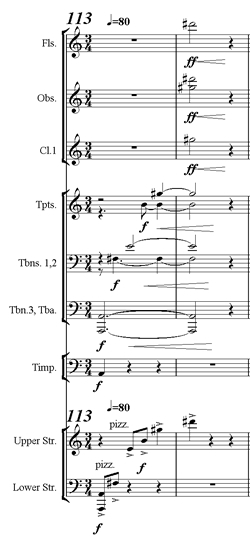

Symphonic Movement #1: High woodwind complete the rising chord in the brass.

Brass

Brass are more homogeneous than woodwind, but less agile. They can play melodic, rhythmic, contrapuntal, and harmonic roles equally well. They also reproduce choral writing better than woodwind; in much early music, brass, especially trombones, simply double the voices.

Horns are best thought of as alto instruments; beginners often place them much too low or let them wander too high. The best arrangement for horns in harmony is: three or four horns, in close position, in the range of the alto voice. Sometimes the fourth horn doubles the first, an octave lower.

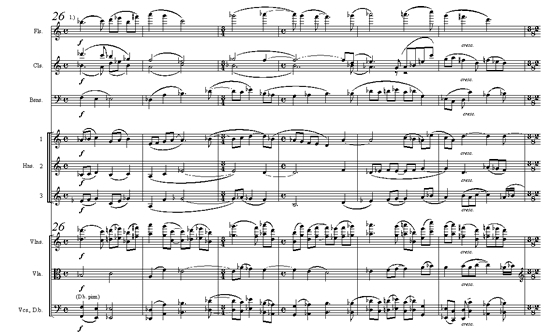

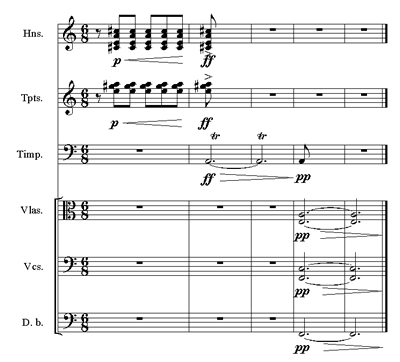

Symphony #5, finale: the three horns here add richness to the texture, without heaviness.

Horns are traditionally divided into high and low specialists, sitting in alternate seats, i.e. horns 1 and 3 are “high”, while horns 2 and 4 are “low”. While all horn players are comfortable in the middle range, when playing at the extremes, the embouchure required takes special effort and practice. Thus, the “high” horns are uncomfortable on the bottom notes, and the “low” horns are uncomfortable on the top notes.

The horns’ lowest notes are best reserved for slow moving pedal passages; they are not suitable for mobile bass lines, which they tend to render ponderous.

Piston mentions that horns are best treated in the general spirit of the natural instrument – for example with a preference for open harmonic intervals like fifths and octaves, and for generally diatonic lines. This remains excellent advice.

Symphony #8: Restricting the horns to octaves on the longer notes keeps the harmony transparent.

Although horns are now of course chromatic instruments, extreme agility is not in their nature.

These observations are also true of trumpets. (Note, however, that horns and trumpets can manage fairly rapid repeated notes.).

Trumpets sound oddly empty in wide spacing; trombones, on the other hand, sound full in both open and closed positions. Trombones in close writing in the baritone register are somewhat lighter than horns, a useful fact to remember when using brass to accompany solo instruments, or the human voice.

Compare horns and trombones in this register.

Muted brass should be considered as a separate timbral family, so different is their timbre from open brass. When soft, muted brass are quite close to double reeds in sound; when loud, their strident sound puts them in a class of their own.

While there are various ways of classifying percussion instruments, it is most useful for the composer to think of them according to their sound, and then classify them into families by register and pitch. For example, metal instruments are normally “wet”, with substantial reverberation, and therefore not well suited to quick, precise rhythms. On the other hand, they can supply background ambiance very well. Wooden instruments are “dry”, best used where clarity and definition are important. Membrane instruments are in between: When low, they can reverberate quite long; as they get higher, their sound resembles that of the wooden percussion.

Percussion can function as:

Accent

Compare the two versions of each chord: Each is presented first without percussion, and then with. Adding percussion sharpens the accents, adding impact and power.

(repertoire examples) There are countless examples of incisive final chords in major orchestral works of the classical period, with timpani added for accent.

Melody

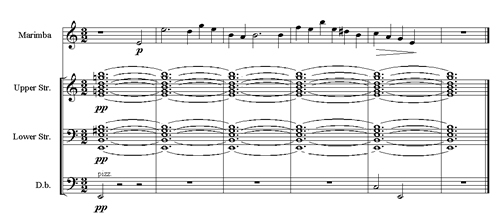

The marimba melody emerges easily over the mysterious chord played by divided strings.

(repertoire example) Shostakovitch, 15th Symphony, Finale, coda (rehearsal #148): The timpani present the passacaglia theme while other, fixed pitch, percussion dance around it. Sustained string chords provide a mysterious background.

Rhythm

The xylophone presents a rhythmic idea.

(repertoire example) Bartok, Concerto for Orchestra, 2nd movement, beginning: The snare drum (playing without snares) presents an important rhythmic theme.

Resonance

Without the quiet cymbal roll, the flute line would sound patchy and empty.

(repertoire example) Dallapiccola, Canti di Liberazione, opening: While a wide-ranging vocal line flows through the various sections of the choir, quiet cymbal rolls provide a haunting background ambiance. Note how the cymbals are not just continuous rolls, but are rather composed in overlapping waves.

Transitional sound between changing dynamics.

Without the timpani roll diminuendo, the contrast between the high brass and the low strings would be much more abrupt.

(repertoire example) Bruckner, 9thSymphony, 1st movement, m. 75-6: A timpani roll, diminuendo, provides a smooth transition between the loud tutti which precedes it, and the very quiet passage which follows.

As a general rule, when percussion is combined with other families in the same plane of tone, it should correspond in register to the music around it.

Writing for voices is a too big a subject for detailed consideration here, but a few words of advice are in order.

Words must be set as intelligibly as possible. Singing, by nature, strongly distorts words in favor of vowels; consonants function mainly as articulation. The rhythm, accentuation, and contour of the vocal line should follow that of the words, well spoken. They may exaggerate, but should not contradict, the rhythm and contour of the spoken verbal phrase. There is also the added consideration that the voice cannot develop a full sound on vowels formed with the mouth closed, like the French “u”. (It is not for nothing that the Italian “amore” is a wonderful word to sing!) Therefore climactic passages must be planned around important words, which also permit the voice to sing out.

Voices need time to open out to their full sound; therefore very agile and/or staccato writing is a rare, special effect.

More than any other instrument, voices require writing in the middle of their range most of the time, to avoid discomfort. Very low and (especially) very high writing should be reserved for special moments.

WHAT IS POOR ORCHESTRATION?

As mentioned earlier, it is actually quite hard to write really bad orchestration, provided the music is playable.

While we will concentrate here mainly on the positive aspects of artistic orchestration, it is worth identifying the main characteristics of poor orchestration:

- Feebleness of effect: Not using all the resources available to create the desired character (e.g. trying to get a percussive effect using only a few woodwinds, and with no use of percussive sounds); creating contradictory gestures (e.g. adding instruments during a diminuendo).

- Aural fatigue: Overuse of extreme registers or very distinctive colors; lack of blend in harmonic masses.

- Grayness: Too much unison doubling.

- Heaviness: Too much doubling, or overloading the low register.

- Consistently dry sound, without any background resonance. (Dry sound can be effective, but not as a norm.)

- Confusion among musical elements: Poorly differentiated planes of tone.

- Formal confusion: Changes of timbre at arbitrary places; changes not appropriate to the degree of contrast required.

- Lack of clear character.