Orchestration – Basic Notions, Pt. 1

ORCHESTRATION AND FORM

All through this series of online books we have repeatedly insisted that any musical gesture’s effect is largely determined by its placement in the work’s span of time. Artistic orchestration also needs to be seen as an integral part of musical form.

Key points, which need to be planned orchestrally in relation to the whole work, include:

- Changes of sound: Changes of timbre must be logical in the musical context. A change of sound creates a formal articulation. The normal place for timbre to change is between phrases, sections, etc. Within a phrase, orchestral changes will normally occur at musically significant moments: motivic changes, climactic moments, and cadences. Changes at other places sound arbitrary.

Compare the first version, where the change from flute to oboe is musically logical, with the second. Ridiculous though it may seem, this problem is common in student work.

(repertoire example) Mozart, Marriage of Figaro, Overture, m. 59-67: Instruments are added throughout the phrase, coordinated with motivic repetitions; the last addition (flutes) arrives as an imitation.

- Accents: moments which attract special attention from the listener. Orchestrally, accents usually require momentarily adding some new sound, or changing the playing technique in some way, e.g. by using double stops in strings. The change must of course be proportional to degree of accent required.

- Cadences: Structural articulations can often be enhanced by some change in the orchestration.

The addition of pizzicato basses underlines the cadence.

- Progressions: Progressions can create momentum and a sense of direction, as discussed in the first volume of this series. Common examples include:

- Crescendi and diminuendi (see example below).

- Gradually rising or falling passages.

- Texture getting thicker or thinner.

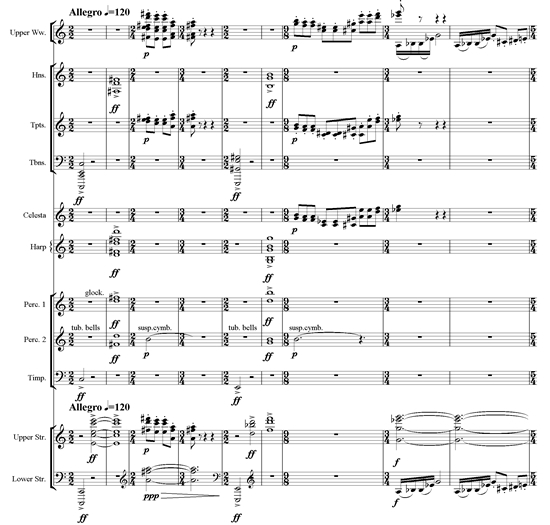

- Gradation of climaxes: Usually one climax, near the end, stands out more than the others. It is important to reserve some unique orchestral resource for this moment.

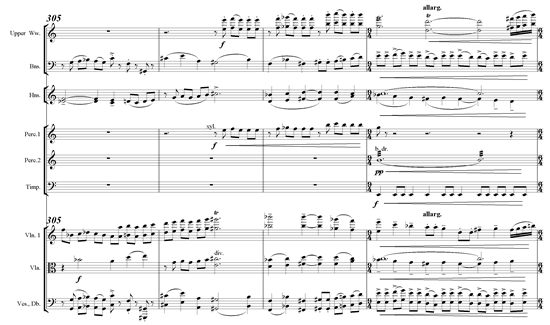

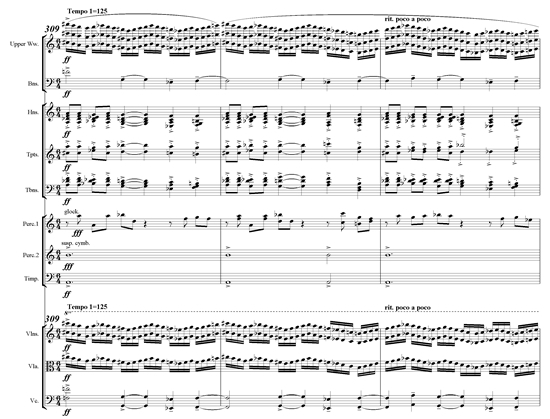

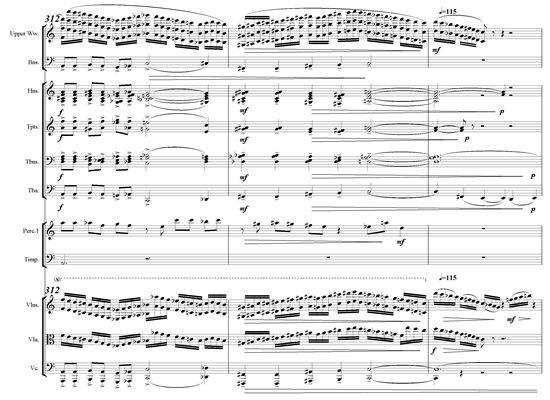

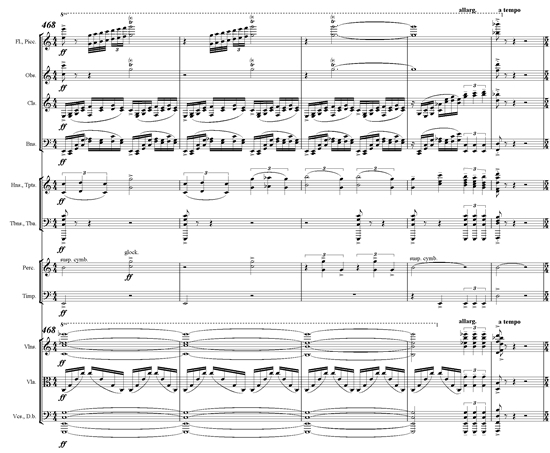

Symphony #7: The main climax of the piece (m. 309) is orchestrally set off by extremes of register, an explosion of rhythmic activity and color in the percussion (glockenspiel, suspended cymbal, timpani), and full brass in quickly moving harmony.

RATE OF ORCHESTRAL CHANGE

Like harmonic rhythm – the rate of harmonic change – the rate of orchestral change has an important impact on the music’s pacing. It is difficult to quantify as precisely as harmonic rhythm, since orchestral changes come in many degrees of salience – adding a unison flute doubling to a line in the violins does not have the same impact as adding three trumpets playing chords. Nonetheless, the rate at which timbres are added or removed, especially within a phrase, can contribute to effects of tension or of relaxation. Such orchestral “speeding up” and “slowing down” normally compliments and enhances the phrase structure of the work.

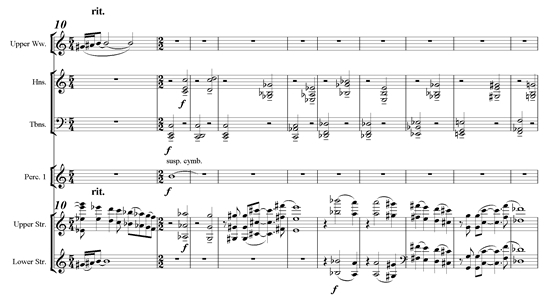

Symphony #6, finale: After a restless beginning, with significant timbre changes every bar or two, the orchestration becomes less volatile from m. 11 onward. This reflects the arrival at a stable presentation of the main theme, following the introduction.

(repertoire example) Mahler, 4thSymphony, 2nd movement, m. 34-46: From m. 34-42, the changes of sound are quite subtle. However, the arrival of stopped horns in m. 43, followed two bars later by the main theme transferred to woodwinds (strings have been playing previously), creates more emotional intensity. In general, the nervous character of this movement is much enhanced by the frequent, prominent, changes of timbre. Compare the beginning of the 3rd movement, whose calm character results from remaining entirely within the string choir.

Degree of continuity/contrast of timbre

The degree of timbral change must correspond to the degree of formal contrast required: A major section break requires more orchestral contrast than a new motive within a phrase. Timbre strongly affects the perception of musical form: Too great a contrast will create an inappropriate break in the music; too small a contrast will deprive the music of necessary punctuation. Beginners often misjudge the degree of contrast between successive passages. While it is impossible to grade orchestral contrasts with complete precision, we will provide some guidelines here for gauging the perceived contrast between successive orchestral phrases. However, first an important caveat: Perceived contrast depends not only on timbre, but also other aspects of the music, such as register, articulation, general texture, etc.

To make our task easier, we will here assume the simplest situation: a phrase with only one timbre, e.g. a melody for flute solo. This will allow us to focus on degrees of contrast between timbres. Obviously, the more other the aspects of the music change at the same time, the stronger the perceived contrast will be.

Here is a rough but useful scale of contrast. We will assume two successive phrases, identical in all ways, except for timbre and transposition, to fit the new instrument’s range. The scale has five levels, from minimal contrast to maximum contrast. Within each group, differences are not significant. For purposes of this discussion, we will refer to strings, winds, and brass as “families”, and flutes, oboes, clarinets, and bassoons, each with their respective auxiliaries, as “sub-families”. As a general principle, timbres which blend well in chords present little or no contrast when heard in succession; timbres which do not blend in chords make for stronger contrasts.

Group 1: contrast is imperceptible or very mild

- Exchange within the same instrument, between different registers, e.g. low flute/high flute (excepting the most extreme registers).

- Exchange between adjacent members of the string family.

- Exchange between trumpets/trombones.

Group 2: mild to moderate contrast

- Exchange within the same sub-family of winds, e.g. flute/alto flute, oboe/English horn, etc.

- Exchange within the same instrument or sub-family, but involving extreme registers.

- Exchange between diverse members of the woodwind family, and in registers which blend well in chords, e.g. clarinets/bassoons in the middle register, flutes/oboes in the higher register.

- Exchange between certain woodwinds and brass, where simultaneous blend would be good, e.g. bassoons/horns.

- Exchange between horn/trumpet or horn/trombone.

Group 3: contrast is more marked

- Exchange between diverse members of the woodwind family, which would not blend well in chords, e.g. low oboe/low flute. Very often these cases involve the oboe.

- Exchange between woodwind and brass: combinations which do not blend well simultaneously.

- Exchange between woodwinds and strings.

- Exchange between brass and strings.

Group 4: contrast attracts more attention than the similarity

The sound is of a completely different nature, e.g. strings arco exchange with strings pizzicato.

Group 5: contrast is extreme

Exchange can only use one aspect of the phrase, e.g. flute vs. snare drum: Only the rhythm can be imitated.

Additional Notes:

- Percussion instruments can be treated as a group of sub-families, following the standard classification into woods, metals, skins, pitched and unpitched.

- Pizzicato strings should really be thought of as a kind of pitched percussion.

- In a passage with more than one plane of tone, contrast will be lessened if the background plane remains constant, e.g. a flute phrase repeated by the oboe, where both phrases have identical string accompaniments.

- If the music uses mixed timbres for one element (e.g. a unison melody for oboe and clarinet in unison), the degree of contrast will depend on whether there are common elements between the two mixtures, e.g. oboe + flute in unison will be closer to oboe + clarinet in unison than simply going from oboe alone to clarinet alone. Of course the prominence of the common element(s) is also relevant. Note that extensive use of mixed timbres makes larger formal contrasts harder to effect, since the colors, not being pure, are less distinct.

- A sudden change from very loud to very soft requires special handling. After a fortissimo tutti, the ear requires a moment to adapt to very quiet music; otherwise the first few quiet notes can pass unnoticed. Often in such cases, one or two instruments will be held over from the fortissimo passage for a few beats, to soften the abruptness of the change.

INTERPRETING THE PHRASING

It is possible to enhance the contour of a phrase orchestrally. While the ordinary ebb and flow of the music will be brought out naturally by sensitive players, in cases where the composer feels the need to indicate such dynamic details explicitly, they can also be enhanced by subtly changing the orchestration. The two most common cases are:

- Accents and highlights: as mentioned above, accents are achieved by momentary additions of one or more instruments, often with percussive attacks (although sometimes just a touch of contrasting color will be sufficient). Normally, what is added should be in the same register as the main line, and proportional to the overall dynamics and character.

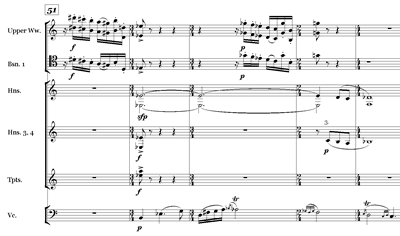

Symphony #4, 1st mvt.: The sfp in m. 51 is greatly enhanced by the 8th note attacks in the 3rd and 4th horns, and in the trumpets.

(repertoire example) Beethoven, 7th Symphony, Finale, 2nd theme, m. 74 ff: The sudden accents in the main (string) motive are much enhanced by reinforcement with wind chords.

- Crescendi and diminuendi: An orchestral crescendo is achieved by adding instruments in a well graduated order, and a diminuendo by subtracting them. It is especially important not to inadvertently contradict the dynamic evolution of a phrase by doing the opposite, e.g. adding instruments during a diminuendo.

Symphony #4, 1st mvt.: The crescendo is orchestrated by adding high oboes and thickening the horns (m.135). At the climax of the phrase (m. 136), extra accent results from the special sound of the highest register in the horns (Eb), adding an extra octave (violas) to the strings, and the timpani chord in m.137. Note also the removal of the oboes and the thinning in the horns for the subsequent diminuendo.

(repertoire example) Beethoven, 9thSymphony, beginning: The magnificent crescendo is achieved by gradually adding instruments: violin 1, double bass, viola, clarinet, oboe, flute, bassoon, etc.

ORCHESTRATION AND DYNAMICS

There is an important distinction to be made between absolute and relative dynamics. Every instrument has some relative dynamic control in every register. However, some instruments, in particular registers, simply cannot achieve certain absolute dynamics. For example, a group of brass playing in their high registers will never be very soft; a low flute can never be extremely loud. The best rule for a beginner is: Orchestrate your dynamics instead of just writing them as textual indications. Especially at dynamic extremes, ensure that the instruments and the registers chosen are conducive to the dynamic level required. As a rough guide, here is a table of what the various families can achieve in absolute dynamics.

| ppp | pp | p | mf | f | ff | fff | |

| woodwind | (x)* | x | x | x | x | x | |

| brass | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| percussion | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| strings | x | x | x | x | x | x |

(* the clarinet can play whisper soft, provided it is not written too high.)What is important in this chart is the dynamic extremes. Strings and certain percussion, (tam-tam, cymbals, and the lower drums) can start practically inaudibly. For sheer power, nothing has the force and impact of high brass plus percussion.

The notation of dynamics is often problematic for beginners. A good approach is to act as though there are only four dynamic levels: pp, mf, f, and ff. First, orchestrate the passage so that the absolute dynamic level desired results naturally from the choice of instruments and registers. Second, think of dynamics as character indications. Choose which dynamic of the above four best suits the passage. Third, avoid the middle dynamics (mp, mf) as starting points: these are what players do when there are no dynamics notated at all. Finally, beginners should avoid writing different dynamics for different instruments; this requires a great deal of experience: Players normally do not see each others’ dynamic indications, and normally aim for approximate balance, unless the conductor specifies otherwise.

REGISTER

Normal

Register planning is essential to good orchestration, since a change of register is obvious even to a non-musician. Most of the time, music is centered in the middle of the range of human hearing (which corresponds to the range of human voices). This is to be expected, because in this register, the human ear easily distinguishes pitch and experiences no strain. If the desired result is a blended sonority, to be perceived as one single plane of tone, the layout of the music within this register normally will follow that of the overtone series: wider in the lower range and more compact getting higher, with no large gaps in the middle – such gaps tend to divide the sound mass into separate planes. On the other hand, where differentiation is needed, as in certain types of counterpoint, such gaps may be appropriate.

(repertoire example) Mozart 40th symphony, 2nd movement, beginning: The quiet, calm effect here results in part from the use of middle register strings, normally spaced(after the wide register tutti which finishes the 1st movement). Note how the register becomes higher during the phrase, creating a sense of gradual evolution.

High vs. low sections

It is advisable not to fill the entire audible range all the time: Occasional passages in the higher or the lower range alone provide valuable contrast and relief for the ear.

Symphony #8: The light, high passage at the start of this excerpt makes the subsequent massive texture, including low brass, an effective contrast to start a new section.

(repertoire example) Brahms 4th Symphony, 3rd movement, m. 93 ff: Following the normally laid out tutti just preceding, the contrast of low and high chords provides a simple but dramatic contrast.

Extremes

Extreme registers should not be used constantly; they fatigue the ear. It is normal, however, for tutti passages to fill a wide range, with the bottom adding fullness and depth, and the top adding brilliance and power. Note that the number of instruments required at the extremes is considerably smaller than in the middle. For example, even in a large tutti, one piccolo in its highest register will penetrate without difficulty.

Symphony #8: The piccolo in its highest register, and the tuba and double basses in their lowest register, are critical to the climactic impact of this passage. The violins are also at the very top of their range (and indeed require very good players). Note also the trumpets and horns: Although not high in absolute terms, they are very high within these instruments’ ranges, creating an effect of intensity and strain.

Hollow Textures

Textures with large gaps can occasionally be quite effective, although the ear tires of this effect rather quickly. This sonority also works better in softer dynamics: Loud passages with holes in the middle tend to sound feeble.

Variations for Orchestra: The empty spacing between the flute(s) and the bass line gives a very distinctive color to this variation.

(repertoire example) Mahler 9th Symphony, 1st movement, m. 382 ff: Extremely widely spaced counterpoint here provides momentary relief from the generally rich orchestral sound.

Registral Progressions

Not all passages stay in one register. Especially when working towards or away from climaxes, often it is effective to create progressions of register, either widening out from the middle in both directions, or else adding more and more high or low material. Such progressions are powerful sources of musical direction.

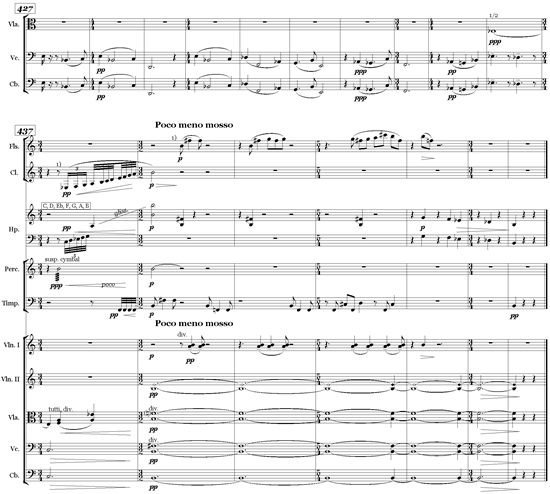

Variations for Orchestra: After the preceding low passage, the rising harp and clarinet (m. 437) give the impression of pulling aside a curtain to reveal something new. The gentle cymbal crescendo adds a mysterious background.

(repertoire example) Brahms 1st Symphony, 1st movement, m. 293-321: The intensity of this buildup comes in part from the gradual progression from the lower middle range towards the high register, at the climax (m. 320).

COLOR

Although it will be clear by now that color is not as important an issue in orchestration as is commonly thought, variety of sound, arising from formal and emotional necessity, is of course essential. There are two main principles which make for effective orchestral coloration:

- The color must have the right character.

- Color is less the result of exotic timbres than of novelty in the context of the piece. Even a familiar timbre like an oboe can sound striking and novel, provided it has not been heard for a while. This is why Mozart’s orchestration is always so fresh, despite its limited number of colors.

SUSTAINED VS. DRY SOUND

It is often remarked that the orchestra has no sustaining pedal. While this has obvious consequences for transcribing piano music, it also points to an important issue in orchestration in general: Resonance.

Resonance is by definition a part of the background layer. In its literal meaning, it refers to echo, the effect of a “live” room. However, resonance can also be deliberately composed orchestrally, and therefore individualized. Although in the history of orchestration, elaborate planes of background resonance only become the norm with the disappearance of the continuo, Bach (e.g. in various cantatas) already shows sensitivity to the way a long held note can enrich the texture. In fact, he goes even farther, and there are numerous examples of such notes used as points of departure for important lines. This particular way of composing with resonance – (others include the lines which dissipate into held notes, and resonance which is intermittent, or which includes some simple rhythmic formula – gives way to more refined ways of using sustained sound in the background to enrich the texture.

(repertoire example) Ravel, Valses Nobles et Sentimentales, Epilogue: The background held notes in the strings, set off by gentle harp harmonics, provide a shimmering halo surrounding the main motives in the winds. This conception of the background as delicate vibration is omnipresent in Ravel. Indeed, Ravel’s orchestral technique is often most sophisticated in his treatment of such sustained sound in the background.

Although it is not good practice to orchestrate for long without sustained sound, occasional dry passages can be extraordinarily effective. Indeed, the distinction between “dry” (=rhythmic) percussion, and “wet” (=atmospheric) percussion is a useful for composers interested in creating variety of character. This dry/wet distinction translates into the need for variety of articulation (staccato/legato) from a rhythmic and motivic point of view.

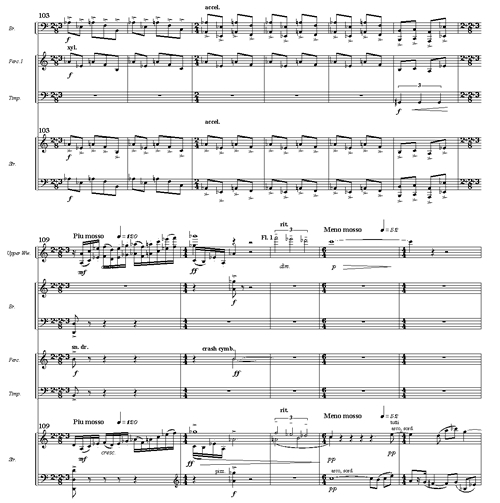

Symphony #3, 1st mvt.: The heavy staccato articulation in m. 103 ff. is broken with the arrival of held notes in m. 110, which introduce a contrasting, legato passage. Note how the former articulation is accompanied by the dry sound of the xylophone, whereas the sustained sounds are introduced by the “wet” cymbal crash.

FAT VS. THIN SOUND; UNISON DOUBLING

Koechlin makes a useful distinction between loudness and volume: By “volume” he means the ” thickness” of a given sound. For example, at any dynamic level, a horn will always sound thicker, or “fatter”, than a violin. Acoustically, thick sounds tend to have stronger fundamentals than thin sounds. Fat sounds occur in the orchestra in two ways: as chosen timbres (e.g. French horn, tuba), and as a result of unison doublings.

Symphonic Movement #1: Note the much richer, fatter sound when the horns enter in m. 104.Unison doublings fall into two types: the instruments involved may be the same or different. If they are the same, the change from one to two instruments is more qualitative than quantitative: It adds more volume than loudness. When different timbres are involved, new colors are created, whose success will depend on the character of the resulting sound, and its appropriateness in context. Since overuse of unison doubling is the beginner’s most common fault in orchestration, a good elementary rule of thumb is: Do not double at the unison, unless there is a definite need for more volume, or unless the particular color is exactly what is needed for the musical character.

BALANCE: SIMULTANEOUS AND SUCCESSIVE

A related distinction, also discussed by Koechlin, is that between simultaneous balance and successive balance. The former refers to which instruments will dominate within a given combination; the latter refers to balance between successive sounds. This is a problem mainly when passing from very thick sounds to very thin ones: The thin sound can seem disagreeable by comparison with the previous richness, even though, heard in another context, it might not be disturbing at all. For example, after a loud, full brass passage, an oboe will sound thinner than usual, by contrast.

As to the first type of balance, Rimsky-Korsakov lays out many excellent rules of thumb; these need not be repeated here. All other things being equal, (i.e. if the force of the instruments involved is fairly equal), here are some additional guidelines:

- The top line normally attracts the most attention.

- The ear normally follows activity: If, say, in the string choir, all the parts except the viola are static, the movement in the viola will stand out.

- As Koechlin points out, too much activity can distract: Normally strings are ideal for accompanying the voice, but if they are playing vigorous counterpoint they will cover the voice much more easily than if they have long held notes. In other words, balance is not just a function of the choice of instruments, but also of what they are doing.