On Teaching Harmony, Counterpoint, Orchestration, and Composition

The standard training for a composer normally includes courses in harmony, counterpoint, and orchestration. But too often students are left with questions about whether, or how, learning these disciplines can help them as composers.

Harmony and counterpoint taught as historical studies – harmony of the classical period, Palestrina or Bach style counterpoint – can be interesting in a musicological sense, but for a composer they sometimes just seem irrelevant.

But these subjects really are essential for a composer … if they are taught in a practical, integrated way. Here I want to make the connections between them clearer, and to focus on how they relate to real-life composition.

The first thing a good teacher needs explain, for any subject, is why it is worth studying at all. So – why should we study orchestration?

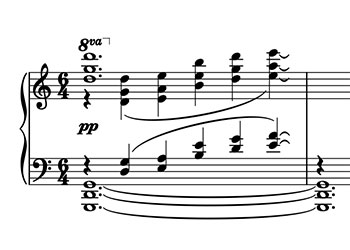

Well, once you get past the basics of each instrument’s range and technique, orchestration is all about timbre and planes of tone. Anybody who has spent five minutes listening to the Debussy Preludes for piano will have noticed how rich they sound. That is because they almost always use multiple planes of tone, made possible by the piano pedal. In effect, it is as though the piano can include more than one single instrument. Think of the “La Cathédrale Engloutie”:

Here the outer parts, sustained as pedal resonance, act as background to the rising line in the middle parts. If we were to orchestrate this, the instruments holding the outer parts would be different from those doing the middle parts.

In ensemble writing, a composer needs to be aware of which timbres blend, and which are more contrasting: again, planes of tone. How do you make the main line stand out from the accompaniment? Contrasting timbres. How do you create a rich background texture without distracting from the foreground? Layered planes of tone. Timbre and planes of tone are relevant in any style of music, since they ultimately are issues of aural perception: how we hear. There is now quite a lot of solid scientific research in this area; a good teacher should be aware of it.

Why study harmony and counterpoint? Well, our western tradition, unlike some others, is not monophonic. Once you have more than one voice sounding at a time, lots of wonderful things become possible, if you understand how the various parts can interact. Harmony is about how the voices meet in chords, how those chords are connected, and how the bass line can be used to create tension and direction.

Counterpoint is the other side of the coin, focusses more on the interactions between individual lines. But harmony and counterpoint are really two sides of the same phenomenon: multi-voice music. If you are writing music for more than one person, counterpoint will give you the tools necessary to make sure that even the secondary lines have some interest, while not upstaging the main lines. Harmony will show you how to organize all the parts into a coherent, well directed whole.

And as you get past the basics, advanced chromatic harmony depends more and more on details of line, often in the inner parts. Advanced counterpoint is seriously handicapped without rich harmony. For example, invertible counterpoint is much easier using 7th chords than if it’s limited to triads: there are so many more possibilities available with seventh chords.

Harmony and counterpoint also relate to orchestration. It is not a coincidence that harmony and counterpoint studies both start out with choral writing. The reason is simple: a choir is a standard, blended ensemble. So a beginning composer doesn’t have to worry about the effects of simultaneous, contrasting timbres on the aural result.

So it makes sense to begin working on writing skills with vocal textures. But the fact that we start with choral textures does not mean that harmony and counterpoint should never include instruments or multiple planes of tone.

Once the student is reasonably at ease with basic vocal counterpoint, it is time to move on, for example with stratified counterpoint, where each layer has a different sound. This might be for several different instruments, or perhaps for different keyboards on the organ. Here is an example.

Each of the three lines here has its own rhythm and motives. Notice also that motives sometimes depend on differences of articulation: each line here has its own distinctive articulation.

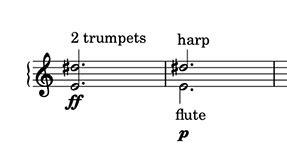

In the case of harmony, once the basics have been mastered, it’s important to look at the way timbre affects harmonic perception. To take a simple example, a major 7th, played loudly by 2 trumpets, is a lot more aggressive than if one note is played quietly by a flute, and the other by a harp.

The latter combination does not blend, and so the dissonance will be perceived as less striking.

This example brings up another issue that is often neglected in teaching: dynamics. Harmony and counterpoint usually focus on pitch, and to a lesser extent, rhythm. But dynamics, as well as tempo and articulation, have an enormous effect on musical character, as we have seen above.

In thinking about musical composition, it’s essential to ask yourself which dimension of the music influences a given passage the most. Working with a blended ensemble, like a choir, puts aside the question of timbre. But in real life, these other aspects of the music are not just details, to be ignored. Sometimes they actually matter more than pitch and rhythm.

This is why all musical training should be thought of as a kind of ear-training. Unless you listen really attentively, you cannot really learn music in depth.

At the minimum, the computer can be used to simulate various orchestral combinations. But listening to a computer is passive. When working on harmony and counterpoint, students should always sing and play their exercises. Nadia Boulanger required students to sing one line while the playing the others, and then to switch to various other combinations of the given lines. This ensures that the student listens actively to what is going on, not just writing dots on paper.

Once we are listening attentively to what we have written, the next step is to concentrate on what sticks out, and why? Sometimes the familiar rules can help, e.g. an unprepared dissonance in 2nd species counterpoint sounds out of place, because the norm there is consonant. But a good teacher should also be able to give examples of other contexts, where the same dissonance could work just fine.

This is because context is an enormous part of how we perceive music: what goes unnoticed in one context can sound very dramatic in another. This is basic psychology of perception: contrast effects. Music is meant to be listened to by humans, so music students should always be guided by what they actually hear.

In his harmony textbook, Roger Sessions speaks of harmonic accent: a chord that sticks out for some reason. It might be because it contains a very sharp dissonance, or because it is far from the home key. Again, context is critical. If the strong dissonance happens at a climax, it may work perfectly; if it happens when the phrase is supposed to be calming down, it attracts attention at the wrong time.

Very often these distinctions are matters of degree: how much does that moment stand out? Many problems in composition come down to recognising that something is too strong, or too bland, for where it occurs in the piece. I call these moments bumps and holes: A bump attracts too much attention in the wrong place; a hole is a dead moment, where interest drops.

This is why it is useful to be able to quantify musical effects, even if only very roughly. Let’s listen to some parallel 5ths:

In the second example, the same fifths are much less salient than in the first example. A good teacher can explain why: the rich, moving line underneath draws our attention elsewhere. Also the last bass notes in m. 2 and m. 3 suggest 7th chords, and give the impression that the harmonic rhythm has speeded up. So we could say that the fifths in the first example are, say, 5/5 on a scale of salience, whereas the second example might rate as 2/5.

So “rules” should not be thought of as absolute, black and white, but more in terms of how much is or is not appropriate, in a given context. The advantage of this “bumps and holes” approach is that it applies to more than one style, since after all, “style” is just a way of describing what is normal in a given context.

So rules are not the main objective when learning writing skills. They are mainly just ways to avoid a few common problems. Just because a counterpoint exercise has no parallel fifths does not mean it is a good piece of music. Many of the requirements for a good piece of music are not even mentioned in the rules. For example, does it develop in a coherent way? How final is the cadence? And so on. The best approach is to evaluate each exercise as a little piece of music in its own right, always making note of what is most salient, and judging its effect, in context.

Speaking of rules, it’s also important to distinguish between rules that are practical constraints, and rules that are just pedagogical. The range of the oboe is not negotiable: the Ab below the treble staff is not playable. But most rules, like those imposed by species counterpoint, have as their main objective simply to limit what the student is working on at any given time. A beginner can’t be expected to concentrate on all musical dimensions simultaneously. Pedagogical rules can and should be superseded, once the student has mastered the given technique. And the best way to move beyond them is, once again, to pay attention to what is perceptually salient, and ask yourself: why? And then, how much is appropriate, here? In this sense, a good composer is always doing research into musical perception. This approach will go a long way towards helping you build up the kind of internal checklist for quality that you need, as a mature composer.

Another essential point: in real music, the various dimensions are always interacting, to some extent. When they all go in the same direction – say, a rising line, more and more dissonant harmony, and a crescendo – the result will be very dramatic. I call this the coordination principle. When you want a more subtle result, you often have choices about which dimension to attenuate.

A teacher who can explain nuances like these is giving the student useful, practical tools, for judging their own compositions. Again, this is why harmony and counterpoint exercises should always be judged as little compositions. Compositions with many constraints, but little pieces of music nonetheless.

These exercises won’t explain everything you need to know about musical form, but all these studies, if well taught, should show you what to listen for, in your own music. They will make your musical ear more demanding and specific, so you can quickly identify and solve problems in your compositions.